The struggles of Latino communities in Washington D.C. highlight the need for inclusive, equitable healthcare access.

Women giving birth at home, turned away by hospitals. Workers excluded from clinics because they didn’t speak English. Children growing up without pediatric care, deprived of the basics simply because they lacked insurance. The stories of community health within the Latino population of Washington D.C. during the 60s, 70s, and 80s are marked by profound desperation and neglect.

Yet, these are also stories of resilience, solidarity, and hope. In 1983, La Clínica del Pueblo was founded as a project of the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN), offering free medical services in a volunteer-run clinic. Five years later, in 1988, María Gómez, along with other volunteers, opened a clinic in a basement, where they served women fleeing war and poverty in Central America, giving rise to Mary’s Center.

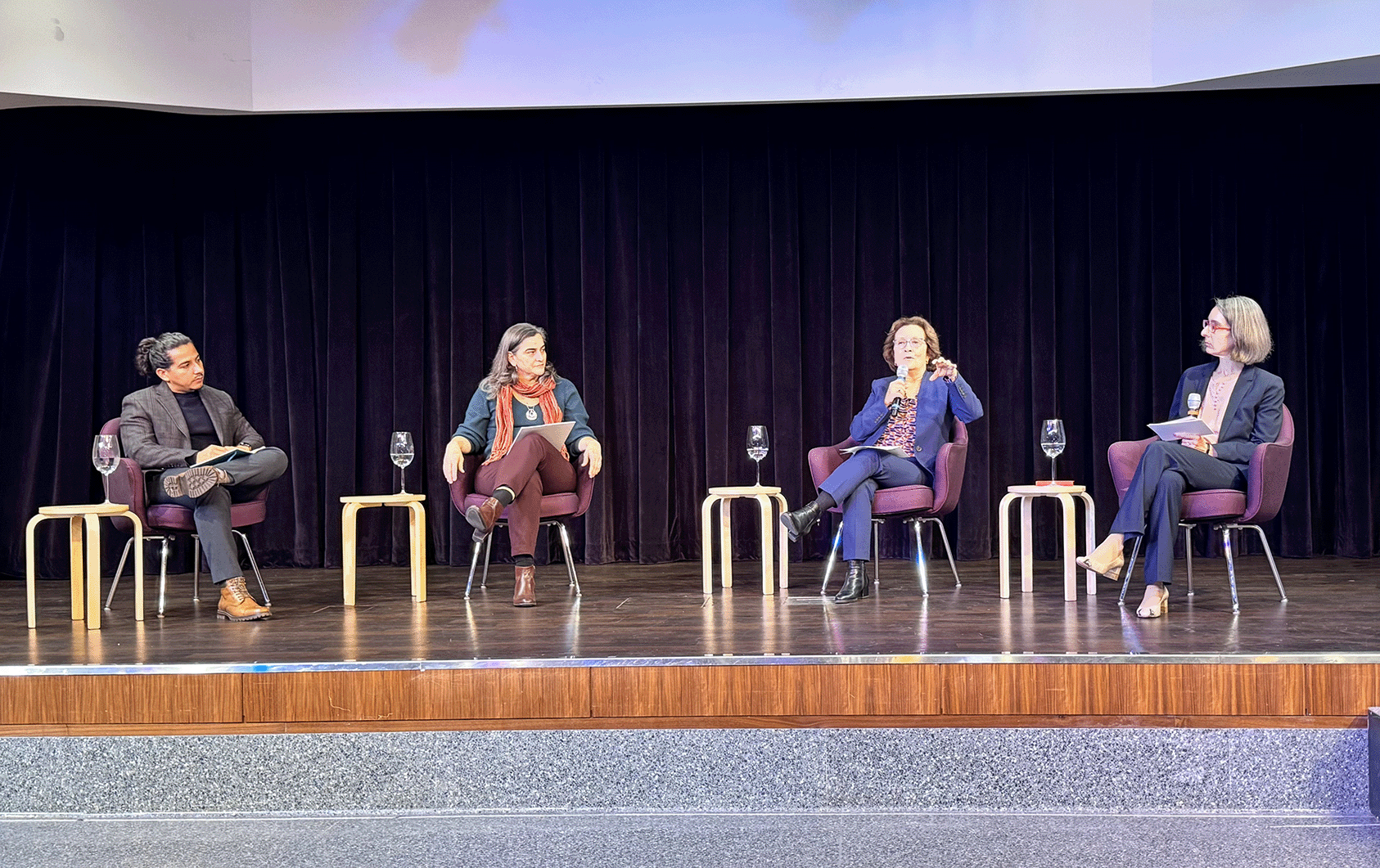

These stories came to life on December 12th at the event Salud Comunitaria: Stories of Latino Health Leaders in DC, held at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Three key voices—historian José Centeno-Meléndez; Suyanna Linhales Barker, Chief Program Officer at La Clínica del Pueblo; and María Gómez, co-founder of Mary’s Center, in a conversation moderated by David M. Rubenstein Curator of Philanthropy Amanda Moniz—shared powerful perspectives on the struggles and hopes of the Latino community in the U.S. capital.

The event showcased the historical challenges faced by Latino communities in Washington D.C., particularly regarding access to health and essential resources. It also explored the perspectives and challenges that still persist, as well as the obstacles the Latino community will need to face in the future.

The Starting Point: Washington DC

José Centeno-Meléndez described Washington DC as a complex and diverse city—a true "melting pot of nations." He pointed out that the Latino community is made up of workers, students, and professionals, all in search of economic freedom or escaping political persecution. This mixture of cultures brings with it a wide range of accents, races, and customs, but also a series of challenges, such as the invisibility of certain groups and their needs.

“It wasn’t until 1970 that the U.S. Census recognized the Latino category,” he explained. “This speaks volumes about the lack of importance given to the Latino community, which was excluded from society.” He added, “Many didn’t know they could access schools, healthcare, or jobs.”

Resources were limited, and support mainly came from churches or community houses. The need to create more robust support systems was evident—a problem that, unfortunately, continues today.

Struggles to Access Healthcare

María Gómez shared a powerful story about the barriers many people, especially within Latine communities, face in accessing healthcare. She described the heartbreaking reality of families who are denied care because they lack insurance or speak little to no English.

She spoke of a mother who had to give birth at home because a hospital refused to admit her due to lack of insurance.

“Women were forced to give birth on their own, in their own homes,” María said. “This is a reality many people face when they are turned away by medical institutions. It’s not just about health; it’s about dignity.”

Her message was clear: healthcare systems must be reformed to ensure everyone has access, regardless of language, status, or insurance situation.

Suyanna Linhales Barker, who worked with marginalized communities in Brazil, spoke about her personal and professional journey after moving to the United States. Reflecting on her work in Brazil, where poverty and racism were common, she shared how those experiences shaped her understanding of structural inequality. Arriving in the U.S., she found herself serving displaced communities and becoming part of them, facing unexpected challenges.

“It’s a different position when you’re not just trying to provide services to a community but also belong to it,” Suyanna said. The public health expert stressed the need to see health as a human right and the importance of changing how systems view and treat marginalized and displaced communities.

“Health is for everyone,” she said. “But the system often excludes and judges those in need, making access to care more difficult.”

A Shared Vision for the Future

The stories shared by José, María and Suyanna paint a vivid picture of the ongoing struggles for healthcare access in Latine community. But they also offer a vision for the future—a future where healthcare is seen as a human right for all, no matter their background. The voices of those on the ground—whether in community organizations, churches, or health centers—are pushing for systemic change, advocating for inclusion, support, and equity in all aspects of life.

As we reflect on the powerful words shared during the Salud Comunitaria event, it’s clear that while much work remains, the collective effort to ensure healthcare for all is stronger than ever. The fight continues, and as Suyanna said, “We are not just trying to help, we are trying to understand.” And in that understanding, we can build a more just and compassionate future for everyone.